In a small room repurposed as a makeshift studio within a house off Pacheco Street, artist Dennis Larkins stands surrounded by his in-progress works, completed pieces and an impressive toy collection. This room is Larkins in a nutshell—a whimsical world where Gumby and the Pillsbury Doughgirl (yes, she exists) stand at attention amidst illustrations and 3D relief paintings replete with the unhinged and familiar-but-not-quite-familiar ephemera of nuclear Americana, sci-fi, Mad Magazine homage, throwback absurdities and cinema paeans.

This room represents decades of experiences, close calls, triumphs, disappointments and a little bit of luck—a laundry list of surprisingly different lives and jobs: a cowboy; Head Start educator; gallerist; Disney Imagineer; scenic designer for the legendary promoter Bill Graham and others.

As Larkins steadily built his career, he emerged as a pivotal part of a lowbrow art movement later popularized by 1980s LA artist Kenny Scharf and others as a humorous sendup of how arts consumers define what is fine or not. Larkins has been a trailblazer in pop surrealism and the lowbrow, an adaptable and nomadic creator and pop culture contributor. He’s still showing, too, both regularly at KEEP Contemporary in Santa Fe and at various events and spaces across the country, like an upcoming San Francisco show later this month.

Now, at age 80, Larkins, who has been in Santa Fe on and off over the years, says he’s happy he made the choice to return permanently to the city to live and work.

This is home.

“What you have to understand about Larkins is that he’s a pioneer,” says KEEP’s Jared Antonio-Justo Trujillo. “People like him or Juxtapoz’s Robert Williams, these guys paved the way for people like me—in my opinion, Larkins is one of the greatest artists of his generation, and not only here, but the world.”

Whether you know him or not, Larkins’ work has absolutely seeped into a broader context of film and popular culture. With a touch of Americana embedded with deeper statements on politics, environmentalism and the absurd notion that the world was once a better place, Larkin lampoons American romanticism while simultaneously confessing to the culture’s magnetism.

“It was the type of experience when you’re excited not just by a piece of art, but by a collection,” longtime Larkins collector Jamie Understein tells SFR of the first time he saw Larkins’ creations on Canyon Road. “A lot of his work has this ‘50s feel to it with cars and [old] computers and clothing; like, it’s of that time period, but at the same time, it can go well beyond. It can have a futuristic feel.”

Think old Coca-Cola ads and sci-fi movie robots with arms flailing; think King Kong and Them! ants; think aliens and skeletons living the dream of the nuclear family. That Larkins developed the style feels fun; that he went into art in the first place feels borderline miraculous.

“My father was a hellfire and brimstone preacher,” he tells SFR during a recent studio visit. “What every kid knows is how they’re raised, and I think that’s a universal truism that your reality is the reality that’s presented to you. Personally, as a sentient being, I had issues, and they were issues in contrast to everything I knew about who I was.”

There comes, he says, a time of awakening, “when you notice there’s a bigger world outside of whatever this created environment all parent-child relationships are built upon—the notion is, you get old enough and aware enough to look around you and maybe see the differences between what people say and what people do.”

For Larkins, that awakening came in grade school, after his family had moved from Abilene, Kansas, to the tiny town of Lamar, Colorado.

“We’re talking about late 1940s, early ‘50s Americana, when…conformity would be the order of the day,” he says. “But I started drawing when I was about 5, at least that I’m aware of in my conscious memory.”

His family life was still religious and strict—like, no dancing or music strict—but Larkins says he and his older brother expressed early creativity through models and diorama for their HO-scale toy rail hobby. Additionally, his mother understood Larkins’ propensity for illustration and introduced him to comic books.

“Highly selected, of course,” Larkins interjects, “like Disney. So I guess Uncle Walt would have been my first influence.”

Later, however, came EC Comics’ horror and sci-fi titles, once Larkins was old enough to choose his own reading material.

“I was aware of comics because, in the downtown of my small town, they had the magazine stand,” he recalls. “Of course, I wasn’t allowed [to read that stuff], which made it more attractive. Then, in 1955, I suppose, I saw my first issue of Mad Magazine, and whatever it took, I dredged up the money to buy that and brought it home secretly.”

It might seem tame now, but Mad was downright radical when it premiered in 1951. For a fledgling artist who’d come up puritanical, it was life-changing. Still, Larkins says, he and his brother kept up with the hobby rail world.

“It was such a pivotal creative vehicle, not only for expanding abilities, but for thinking about the world and the history that led to who we are and where we came from,” he says. “Also, as I got older and would share what we were doing in our little basement studio with friends, I was particularly interested in sharing with female prospects. It was a great chick magnet, you might say. I got to show off my skill sets.”

Models and diorama also gave Larkins his first tastes of positive reinforcement for things he’d created—and the desire for that feeling doesn’t really go away, he notes. Thus, when he began attending the Otero Junior College in La Junta, Colorado, in 1959, he took latent artistic ambitions with him, despite his attendance being predicated upon playing football.

“It was my first foray into the extended world and they had a lot of students from other places,” he says. “It was mind-expanding.”

He wouldn’t last in the football department, but when he made his way to the school’s art classrooms, something stirred. Larkins joined the theater and visual arts departments. In retrospect, he says, Otero’s available arts classes were minimal, but they led him to educator JF “Buck” Burshears, who worked for the school’s Koshare Kiva—today known as the Koshare Indian Museum.

“He always had a cigar in his mouth, but I don’t remember him ever lighting it,” Larkins recalls of Burshears. “He always chewed on it, which was disgusting, and he was this gruff sort of guy. And he loved New Mexico art.”

Burshears was the leader of a Native dance troupe that regularly toured into New Mexico, and Larkins traveled with him from Colorado to Taos. Larkins says that’s when he learned about seminal New Mexico movements such as the Taos Founders and Santa Fe’s Cinco Pintores, and calls the period his “first love affair with Northern New Mexico’s culture.”

During junior college, Larkins sojourned to Taos during the summers with a few bucks in his pocket from temporary farming jobs he’d take during the year, then stayed in New Mexico soaking up the arts until the money ran out before he limped back to Colorado penniless, but all the richer.

By 1963, Larkins had wrapped up his schooling at Otero and transferred to the Kansas City Art Institute on scholarship. The following years were a whirlwind that found the artist both grappling with a changing America—the ubiquity of rock music, the assassination of JFK, the ongoing Civil Rights Movement and so on—and learning myriad artistic techniques. Painting remained his main interest, however, and he was recommended by an art institute professor for a summer contest from Yale University—his brother’s alma mater—that gave students from across the country a chance to attend the institution’s prestigious summer program. Larkins won and headed east in 1965, which he calls “the single biggest thing that had happened to my creative mind.”

Sequestered in a Yale-owned manor in Connecticut, he and a gaggle of roughly 40 other artists convened to spend their days painting and being critiqued by fine arts educators.

“We had the best instructors ever, and they were inviting people who were already, within the context of being young artists, trying to establish themselves,” says Larkins. “I wasn’t even interested in that—I was interested in expanding my learning of what was possible.”

At 20 years old, this was also when Larkins first experienced the New York arts scene and when he first started to develop a sense of self as an artist, including a penchant for landscapes with strange and offbeat compositions that make use of bold, swooping colors. Larkins says he was offered a grad school spot at Yale but couldn’t swing it financially; then, San Francisco Art Institute rejected him because the school wouldn’t take mid-term students. In the end, he landed at the MFA program at University of Colorado in Boulder in 1966.

That lasted roughly a year. New Mexico, meanwhile, kept calling his name. Though Taos had been a favorite destination when he was younger, Santa Fe felt more alive by that point. He and his first wife arrived in town in a beat-up ‘50s pickup with practically all of his art school output and her horse in tow in 1967. Broke and young, they lived for a time in a dilapidated adobe out in Chupadero—one that didn’t even have floors, which required Larkins to lay his art school canvases across the packed dirt like emergency linoleum. And he painted.

“I was familiar with painting in Northern New Mexico in places like Santa Fe and, of course, Taos,” he says. “I was familiar with people like O’Keeffe and Mabel Dodge Luhan and John Sloan and all the radical literati and painters of the 1930s who, at the time, would come out to New Mexico. My thinking was, coupled with the same notion of wanting to do something my contemporaries weren’t doing, all these cool people did cool stuff, and a lot of it, but that doesn’t mean everything that could be done had been done.”

His first solo show of landscapes and figurative pieces that year took place at a space on Canyon Road called The Painter’s Gallery. He also met his first-ever patron, Allan Swartzberg, who would collect nearly 40 pieces over the years that followed.

“Any amount of money is success to a young artist,” Larkins says with a laugh.

The early 1970s brought regular gallery showings and sales enough to buy a little place out in Embudo near the river. He participated in juried shows with local artists at the New Mexico Museum of Art and even managed to open his own Canyon Road space, Larkins Gallery.

“It was a dynamic time,” he says. “A lot of artists who became well-known got their start at the time. Larkins Gallery didn’t last long, but for a season, it was a hopping little place.”

There he showed works by the likes of legendary Santa Fean Tommy Macaione—with whom he’d dabble in plein air painting from time to time—as well as Dennis Culver and Jim and Holly Wood.

“I wanted to get Fritz Scholder to show with me, but he had other commitments,” Larkins says. “But he sent one of his students over to show—TC Cannon. He was doing some really cool stuff, kind of early pop surrealism.”

Yet, making a go in Santa Fe proved rough. Larkins divorced and got remarried by 1972, then left for Berkley to visit his second wife’s family in 1973.

“The idea became to regroup, get a little job, make a little money and then come back and get into painting again, but life has a way of intervening,” Larkins says.

The couple (Larkins’ wife asked that her first name be withheld) stayed in the Bay area for years to come because, as it turns out, 1973 was a banner year for Larkins. Previously, his brother had worked a union scenic design job for the San Francisco Opera, and Larkins cold-called the shop to try to get hired himself. It wasn’t a union or even high-paying gig, but Larkins took a position tidying the shop, answering the phones and other general scutwork.

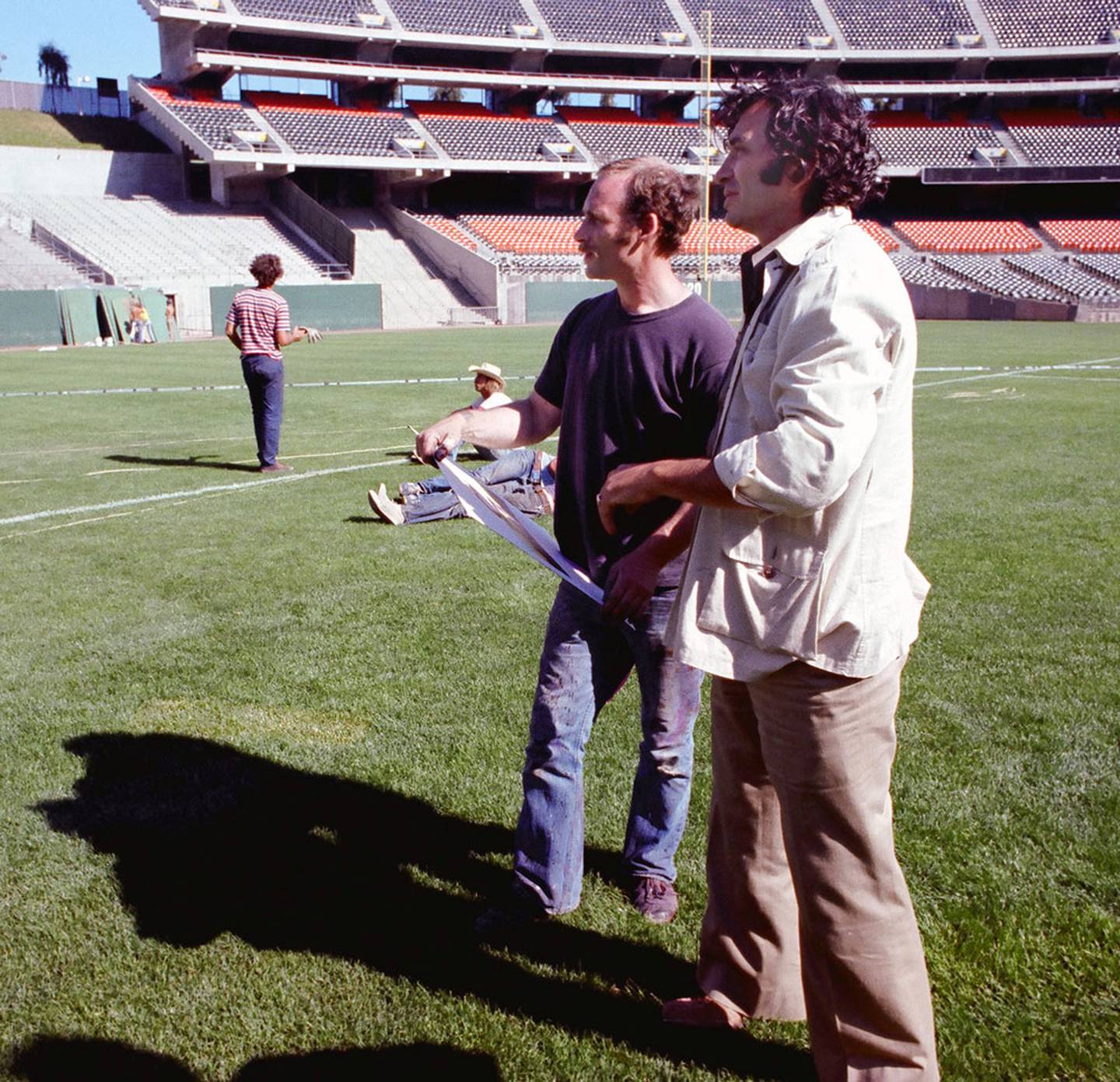

Meanwhile, his wife’s brother was working for iconic rock promoter Bill Graham and had overheard a conversation about needing a backdrop for an upcoming show featuring the band War. Larkins’ brother-in-law chimed in, saying that he knew just the artist to get the job done.

“When the phone rang, I said, ‘No problem,” Larkins recounts. “I’d never done anything like that, but it was basically taking an album cover and blowing it up to 20, 25 feet. I went out and bought the album, and it was fortunately simple, then I hired the shop goods person [from the San Francisco Opera] to sew up the backdrop, one of the journeyman scenic artists to help, my boss…it was my very first backdrop, and we had to whip it out over the weekend.”

The following Monday, Bill Graham’s people showed up to pick up the backdrop.

“I don’t think I’d even asked about money,” Larkins says with a laugh. “But they handed me this envelope of cash, and it was $2,000 inside. From that second on, I became Bill’s go-to background guy.”

In many cases, backgrounds were recreations of album covers, but as time went by, Larkins’ designs grew to be more and more sophisticated—looming dinosaurs towering over crowds or Mount Rushmore, recreated in all its weirdness, hugging the edges of the stage. Larkins’ designs for Graham’s storied Day on the Green festivals in Oakland remain some of the most iconic in rock history—including a legendary Stonehenge set for a 1977 Led Zeppelin performance that was lampooned in Christopher Guest’s 1984 comedy classic This is Spinal Tap.

“I saw that movie at the Jean Cocteau when it was just a regular movie theater,” Larkins says, “and I was practically on the floor because it felt so personal.”

After that, he says, he called the Spinal Tap production company to let them know he’d seen the film and to offer his services. The receptionist to whom he spoke swore up and down the tiny Stonehenge bit was not a reference, but the writing was on the wall. In the years that followed, Larkins went on to work with plenty of other big names, including The Rolling Stones and Jimmy Buffett; he even created the cover art for The Grateful Dead’s 1981 record, Dead Set, as well as sought-after posters for events still uttered in conversations about rock history.

Still, Santa Fe and a serious painting career called to him. By the mid-’80s, he owned a house on Baca Street and was producing landscapes again using methodologies he’d developed while working in stagecraft, many of which—such as layered dimensions and painted reliefs—still find their way into his work today.

Even so, opportunities in Los Angeles pulled Larkins back to California in 1987, where he worked with special effects company Spectra F/X alongside people from his rock show days. This stint included film and television work for movies such as Tim Burton’s Batman 2 and shows like Grizzly Adams. Based on that, he even obtained a coveted job with Disney’s Imagineering department at Walt Disney World in Florida, where he designed stage shows both for then-new adult-focused nightclubs at the park’s Pleasure Island locale (which is still there) and for themed stage events within the park’s more family-oriented areas.

Next came positions for then-in vogue theme shops, like the Warner Bros. Studio Store. In the end, one last contracted job for Disney that never actually came to pass allowed Larkins and his wife the financial runway to make it back to their beloved Santa Fe. They’ve been here full-time since 2007.

“We didn’t need to be in LA anymore, and it was also the beginning of this digital age where you didn’t need to be anywhere for that work anymore,” he says.

He started showing in local galleries, like the now-defunct Skeleton Gallery, as well as Pop—and selling quite well. He also hit upon the style for which most might know him today. With a healthy dose of romanticized Americana as seen through the lens of darker imagery, such as war, nuclear weaponry or even the medical industry, Larkins uses familiar imagery to cloak more subversive political content.

“I refer to it as a commonly shared visual vernacular,” Larkins told SFR in an interview last July, “meaning that images from popular culture and our shared past are sort of combined together to create that visual vernacular we share, where it’s possible to communicate through the use of images pulled from their original context but with embedded meaning.”

Today, Larkins shows exclusively in Santa Fe at KEEP Contemporary, a space known primarily for lowbrow art, pop surrealism and similar works.

He’s got a show coming up at San Francisco’s Haight Street Art Center later this month, plans for future Santa Fe shows and upcoming poster and album art for bands such as Moonalice.

Collectors are still after his work.

“We own nine pieces—not a disgusting number,” says Understein with a chuckle. “They’re all close to our hearts.”

Understein’s wife Jonna adds, “Knowing Dennis and getting to know what a great person he is really makes them special to us. We still stop and look at them and give them time.”

Larkins, meanwhile, has no plans to stop. The rock ‘n’ roll days still course through his veins alongside memories of art school, Mad Magazine and old railroad models.

“I always have a next,” he tells SFR resolutely. “I’m an old rocker. I still love this.”