Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are in dire straits. With the market in a severe downturn, it’s safe to assume the NFT bubble has well and truly burst.

It was never clear why these digital collectables traded for such large amounts of money. Now they mostly do not. What’s behind their turn of fate? And is there any hope for their future?

What are NFTs?

Non-fungible tokens are a blockchain-based means to claim unique “ownership” of digital assets. “Non-fungible” means unique, as opposed to a “fungible” item such as a five-dollar bill, which is the same as every other five-dollar bill.

But just because an item is unique that doesn’t make it valuable. Digital assets are easily copied, so an NFT is essentially a receipt showing you have paid for something that other people can get for free. This is a pretty dubious basis for value.

The two most traded sets of NFTs are the Bored Apes collection created in April 2021 and the CryptoPunks collection launched in June 2017.

Both sets consist of 10,000 similar-looking but unique figures, distinguished by differing hairstyles, hats, skin colors and so forth. The Bored Ape character seems derivative of the drawings of Jamie Hewlett, the artist who drew Tank Girl and Damon Albarn’s virtual band Gorillaz. The CryptoPunks are even less interesting.

Why did people buy NFTs?

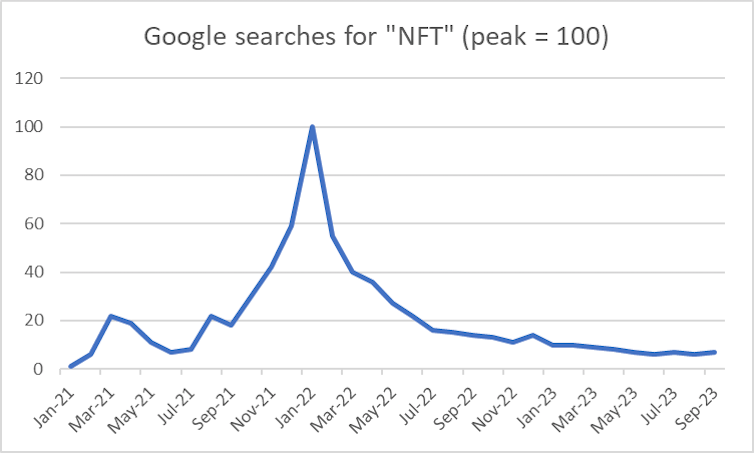

Although the first NFTs emerged around a decade ago, the trend really started to take off in 2021. And for a time NFTs were very fashionable.

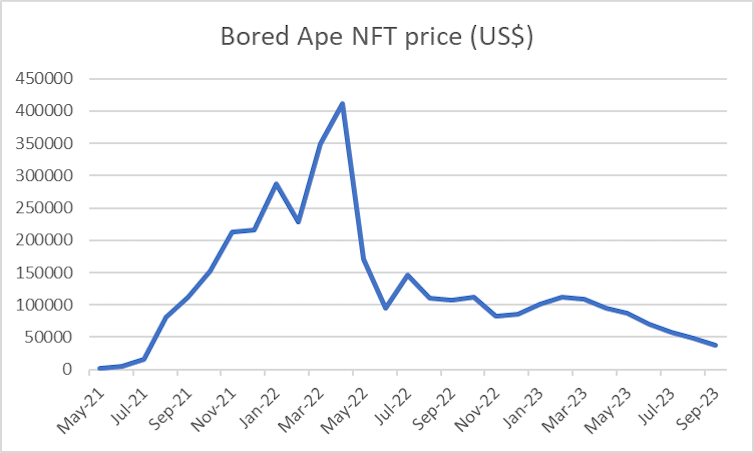

Even the venerable auction house Sotheby’s, founded in 1744, jumped on the NFT bandwagon. Sotheby’s sold 101 Bored Ape NFTs for more than US$20 million in September 2021. They’re now facing a lawsuit from a disgruntled buyer.

As with Bitcoin and similar speculative tokens, the primary driver for buying NFTs was greed. Seeing the initial price rises, people hoped they too could make huge profits. NFTs are essentially a superficially sophisticated form of gambling. Like Bitcoin, they have no fundamental value.

Generally, one would only profit from buying an NFT by finding a “greater fool” willing to pay even more for it. So there was never a shortage of people – including some quite famous ones – talking them up and hoping to instill a fear of missing out.

Eminem bought a Bored Ape that looked a bit like him. Rapper KSI boasted on Twitter about his Bored Ape rising in price.

For a while there were large increases in the prices of many NFTs. But like all speculative bubbles, it was likely to end in tears. Although it’s almost impossible to predict when a bubble for a speculative asset will burst, we have seen this process play out before.

Centuries ago there were the Dutch tulip, South Sea and Mississippi bubbles. Around 1970, there was a speculative bubble in the shares of nickel miner Poseidon. Then came the Beanie Baby and dotcom booms of the late 1990s – and more recently, meme stocks and Terra-Luna cryptocurrency.

The NFT crash

Punters now seem to be as bored with NFTs as the apes. Google searches for “NFT” – which grew rapidly through 2021 – have fallen away dramatically. Trading volumes have collapsed.

One high-profile example is an NFT of the first tweet by then-Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey. Crypto entrepreneur Sina Estavi bought this NFT for US$2.9 million in March 2021. When he tried to sell it a year later the top bid was US$6,800.

What drove the NFT collapse? As well as losing their novelty, the market was hurt by the large falls in the price of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency, as well as the collapse of the FTX exchange and publicity given to scams.

Beyond that, the lifting of COVID lockdowns meant people who began trading NFTs now had other ways to pass their time. And higher interest rates from mid-2022 made most speculative assets seem less attractive.

Collectively, all of these factors made NFTs seem like a riskier proposition. Prominent people started jumping off the bandwagon. Some of KSI’s later tweets lament the losses he suffered from his gambles.

Last year, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced, when he was chancellor of the exchequer (their equivalent of treasurer), the Royal Mint would produce an NFT. The plan has now been abandoned.

Some foolish people had even taken out loans using the “value” of their NFTs as collateral. When the lenders wanted the money back, they were in trouble: forced to sell their NFTs, they got back much less than they’d paid. Fortunately, there weren’t enough people like this to lead to a systemic problem in the financial sector.

Gone for good?

NFTs probably won’t completely disappear. Some subjects of past bubbles are still around. Tulips are still grown in the Netherlands. Poseidon shares, which ran up from 80 cents in September 1969 to $280 in February 1970, are still listed (and currently trading for 2 cents).

But unless some actual use is found for them, NFTs are likely to fade further from public discussion, with their prices increasingly trending down (although the occasional blip up may give die-hard fans some hope).

They will probably join the Dutch tulips and dotcoms in the history of speculative follies.![]()

Article written by John Hawkins, Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You might also be interested in: