Freddy Taylor says serving time at the now-former Guelph Correctional Centre started out as a very dark period in his life, but ended with a renewed passion for life and art.

Taylor, 78, was taken from his home in Curve Lake as a child and forced to go to the Mohawk Residential School in Brantford, Ont. After leaving school, he said, he turned to alcohol and then got involved in criminal activity.

Taylor said he doesn’t recall dates well, but he can confirm he was in jail from the mid-1970s to sometime in the 1980s. During that time, he helped form Native Sons, a group of Indigenous men who helped him and others at the centre to work through trauma in their lives.

“We were happy because [in] the Native Sons group, we talked about everything — alcohol, drugs, how we felt being locked up and being taken away to residential schools. Everything,” Taylor said.

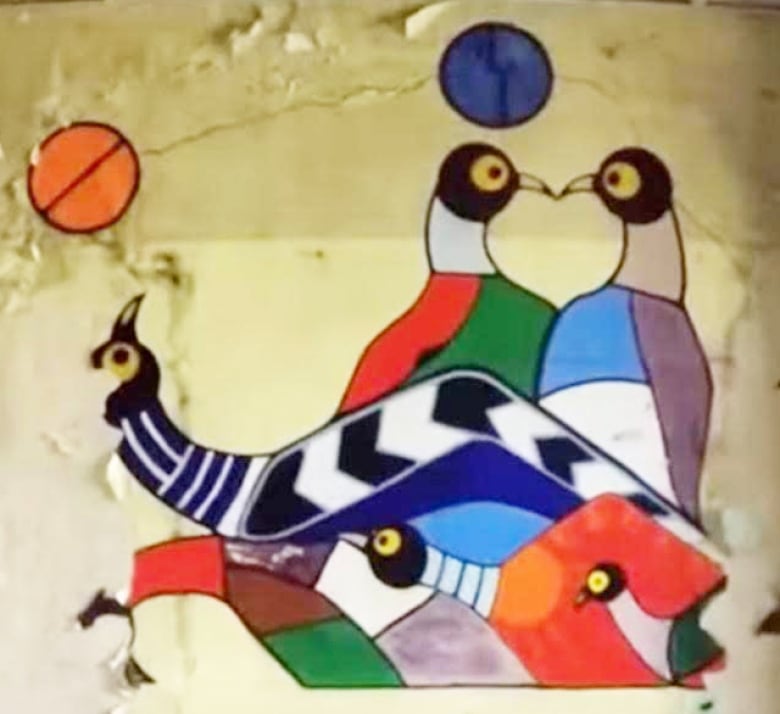

He said many men would create artwork and the group was given permission to paint three murals in the room they used for meetings in a building called the lower assembly hall.

“We planned about what we should put on there and the Guelph reformatory person that was looking after that let us do that after almost a year. And we fought for it,” Taylor said in a phone interview from the Whetung Ojibwa Centre in Curve Lake, north of Peterborough, where he continues to work on his art.

“We took our pain and anger out, and put it on the wall.”

Advocate wants to save murals

Brian Skerrett, a heritage advocate in Guelph, wants those murals saved.

Skerrett is the former chair of the city’s Heritage Guelph committee and continues to research the reformatory’s history. He noted that some of the buildings on the former jail grounds are designated for heritage preservation, but not all of them. That includes the building where the Native Sons met in the lower assembly hall.

He said he finds that “strange because of the whole history of the Native Sons. I mean, the fact that those murals exist is important. The reason they exist is, that room was dedicated to Native spirituality and allowing the Native Sons to explore their own heritage.”

“That makes it really important to recognize. We’re not celebrating, but we’re commemorating. I think that’s important.”

The Native Sons program at the former correctional centre was started in 1977 and it served as a model for similar programs at other institutions in Ontario.

A 1993 report called “The State of the Justice System for Aboriginal Peoples in Ontario” that was created for the Ontario Native Council on Justice pointed to the Guelph program, and said similar ones had been set up at six other institutions.

Taylor said he volunteers as part of a Native Sons program at the Central East Correctional Centre in Lindsay.

Video shows murals still exist

The former correctional centre closed in 2001, in part because it was too costly to maintain the property and buildings. It has now been deemed surplus land by the province, which owns it. The buildings are currently under the care of Infrastructure Ontario.

A request by CBC News to go into the lower assembly hall to see the murals was denied because of health and safety concerns.

Over the years, Skerrett said, there had been rumours that artwork on the walls in the former correctional facility had been painted over by film crews that have used the site.

But in 2021, an urban explorers group called Edge of our Youth posted a video to YouTube showing the murals inside the lower assembly hall. (It should be noted it’s considered trespassing to enter the former correctional centre’s buildings without permission.)

Skerrett said the video gave him hope because it showed the murals still existed and offered a glimpse at their condition.

The larger mural appeared to have peeled around the edges, but the two others were largely intact.

“I went, ‘Oh my heavens, it’s still there. That’s fantastic,'” Skerrett said. “That was the first ‘a-ha’ moment connecting the dots saying, ‘Yes, those murals exist.'”

Murals can’t be moved: Infrastructure Ontario

Catherine Tardik, a spokesperson for Infrastructure Ontario, said an assessment has been done of the artwork in the lower assembly hall and it was deemed it “does not warrant inclusion into the Ontario Art Catalogue.”

The report notes the murals’ style “is typical of Indigenous or Indigenous-inspired works from the 1970s or 1980s and the artists are unknown,” Tardik said in an email.

“The art is painted directly onto structural and load-bearing walls. As such, it is not possible to remove or relocate, as any attempts to remove these pieces would carry the risk of further damage to the murals, the building or potentially, the workers.”

Murals ‘worth preserving’

While the province says the artists are unknown, Taylor said he’s one of the people who helped plan and paint them.

Another artist believed to have been involved is Richard Bedwash, who was born in Hillsport near Thunder Bay in 1936 or 1937 — different galleries list different birth years for Bedwash — and was an inmate at the Guelph jail. He died in 2007.

Judith Nasby, former curator of the Art Gallery of Guelph, remembers going to see Bedwash and even took him art supplies. His artwork is described as woodland spirit art and is colourful, and Nasby said at least one of the murals, if not two, are reminiscent of his work.

“I was amazed at the quality of the work, the care with which he did his drawings … black line drawings with the bright colours of filling in between, in the style of Norval Morrisseau,” she said. The Art Canada Institute said Morrisseau is considered to be the Mishomis, or grandfather, of contemporary Indigenous art in Canada, and was known for using bright colours in his pieces about traditional stories and spiritual themes.

Nasby said she commissioned Bedwash to do 19 legend paintings for the University of Guelph’s collection, and those pieces were shown at the university and were also on tour as part of a mobile exhibit.

Nasby said that in her opinion, the murals inside the former reformatory are significant and should be preserved.

“They’re an example of an incarcerated person with the help, we think, of other incarcerated men to express their spirituality in this way,” she said.

“The reason they did it is because they said that there was a Christian chapel on the grounds but there was no place for them to share their culture, their spirituality and to really socialize in that important way. So I think simply, as an example in Canada of this kind of energy, and desire and importance it was to them to create this space, it’s worth preserving.”

‘They should be documented’

Skerrett hopes that by bringing the murals to the public’s attention, something will be done to preserve them.

At the very least, he said, “they should be documented, they could be reproduced.”

Taylor said he “would love to see them preserved somehow, but I don’t know how you can preserve it.”

Ultimately, for Taylor, the bigger legacy is the Native Sons and how the group has spread.

“In the [United] States and Canada, you can go to any prison and ask if there’s a Native Sons group and they’ll direct you to it,” Taylor said. “That is how powerful our creation became.”