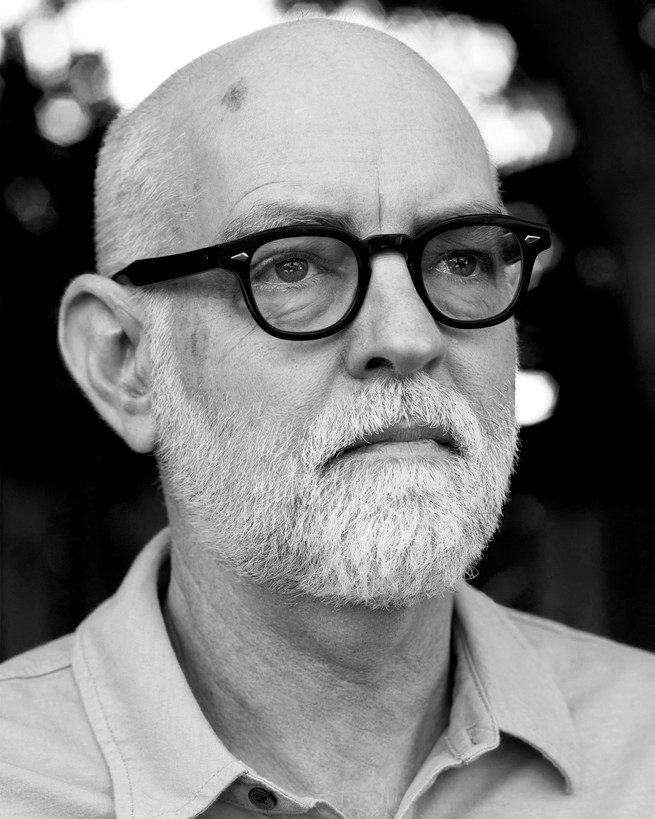

Across five decades, the cartoonist Daniel Clowes has written about a wide array of outcasts: the high-school best friends wrestling with their transition into adulthood; the middle-aged grouch searching for the daughter he never knew; the sex-obsessed malcontent fixated on his ex-girlfriend; the many other dropouts, weirdos, and natural-born screwups who feel drawn from real life. Clowes, who began making comic books in the 1980s as part of an artistic underground fermented during the enforced patriotism of the Reagan era, swiftly became associated with the emergent citizens of Generation X—those authenticity-obsessed, society-rejecting cynics who seemingly wanted nothing more in life than to hang out while avoiding responsibility and other human beings. His characters couldn’t hold down jobs. They didn’t have healthy relationships with their parents. They were like every slacker from your high school whom you suspected had the ability to get it together—but, like, whatever, man.

But what if those outcasts grew up, shedding their cynical armor and actually getting their life in order? The titular protagonist of Clowes’s new graphic novel, Monica, is a woman defined not by defensive misanthropy but by a flinty resilience that propels her to find real meaning in her life. After surviving a chaotic Bay Area childhood in which she’s abandoned by her parents, Monica manages to find some stability as a young woman, and then embarks on a long and often unsatisfying quest to reconnect with her mother and father. Her journey takes many surreal twists: Ghosts are involved, as is a bizarre California cult and—because this is a Clowes story, where doom is never far off—the literal apocalypse. For a book that’s barely 100 pages, things get a little hectic.

Monica shares some DNA with past Clowes heroines such as Ghost World’s acid-tongued Enid Coleslaw, but she’s also different: more ornery and self-sufficient, less naive about other people, equipped with a survival instinct that keeps her chugging along through her life’s many dips and peaks. For a short time, she leaps up several tax brackets by founding a candle company that makes her a household name and is acquired for a nice payday, before she eventually loses all of her money after entrusting her estate to a dopey slacker friend. Not that it bothers her too much: “For all its perils, though, success can in its earliest stages reveal to you the most authentic version of your true self,” she thinks while hanging out with some of those dopey friends. Whereas the screwups of Clowes’s earlier stories tend to see the world as permanently stacked against them, Monica’s ascent shows her that she’s made of tougher stuff—that she can adapt and adjust as she grows older, rather than doubling down on her own biases.

In Monica’s trajectory are some parallels to Clowes’s own life. He’s arguably the most famous alternative cartoonist of his generation—as in, someone who didn’t make their name drawing superhero comics. But, as he told me in a recent video interview, he knows how ephemeral recognition can be, and that understanding informed Monica’s maturation. “You’re around studio heads and people who have private chefs, and you start to think, What would it be like if I were them?” he said, of his brushes with this kind of perspective-altering accomplishment. “It feels very terrifying, very identity-fracturing—so imagining myself on a different tier, it’s almost like her success is nonsensical.” As a result, Monica seems to have no doubts about walking away from her material comforts to track down her parents and unpack the tumult of her early years.

This acclaim can also be extremely relative: Clowes has been able to support himself as an artist, but he is very aware that the comic books he makes are still a niche medium. (In a 2015 interview with The Comics Journal, he said that he had never met another adult who knew his work: “I spend a lot of time with sort of average educated people, like the parents of my son’s friends, and they have no idea what I’m talking about when I try to tell them what I do.”) His success, he told me, “feels very nuts and bolts, as opposed to that kind of oddness that must happen when you make a living the way [Monica] is.”

In 2002, Clowes earned an Academy Award nomination for co-writing the screenplay for the film adaptation of Ghost World (with the director Terry Zwigoff). But he has almost exclusively stuck to comics rather than writing novels or transitioning into film and TV, as many other comic-book writers and artists have done. And although producing a comic book generally involves a range of discrete tasks—a typical comic might credit a writer, an artist, an inker, a colorist, and a letterer—Clowes remains responsible for every aspect of his work. For this, he credited his early engagement with the comics of Robert Crumb, who also exerted this method of total control. “I thought, That’s what you have to do—you have to be transmitting something into the world that is completely yours,” he said. “To me, if it has any value, it’s in getting to see the world through somebody’s vision, and not through the diluted vision of several people.”

Perhaps this insistence on maintaining tight authorship is why Clowes’s books have never been the sort that prompt a half-hearted “Hmm, interesting.” His stories demand real attachment, and the more time I spent with Monica, the more I felt moved by the emotional ambition of its decades-long narrative. Clowes observes his heroine’s life from birth to death, as she comes of age during the permissive hippie generation, makes her nut somewhere in the ’00s, and—after locating some answers about her parents—winds down in present-day small-town America, where she accepts that some existential quandaries will remain forever out of reach. “I liked the idea that she’d become a self-determined person who also has an identity crisis,” Clowes said of Monica’s arc. “That seemed to be a truthful way to deal with how I would see her through a lifetime.” Following her as she matures, Clowes explores what it takes to exist—and possibly even thrive—in an ever-evolving society. Monica may not always do the right thing, but, by the story’s end, she’s able to see herself with a measure of sincere clarity.

This, too, is a change from the typical Clowes narrator, who usually remains a hater. Instead, Monica finds herself learning to tolerate other people over the years, even when she finds them obnoxious. “At this point, I get along with everybody,” she thinks to herself in her retirement. “Who am I to be judgmental?” She’s living among “nature grannies,” “rich golf assholes,” MAGA supporters, and “all the beautiful, crazy women … who make America’s geometric turquoise jewelry and heron-based graphics”—yet she’s able to coexist, mostly respectfully, with them. It’s a far cry from the standoffish mentality that many of Clowes’s earlier characters espoused, and a striking shift toward a gentler perspective that arrives when your life turns out very differently than you’d imagined.

This abating edge is partly due to shifts, big and small, in the real world. Notably, Monica is Clowes’s first published work since Donald Trump was elected to the presidency. Clowes thinks his trademark spiky humor, discernible in earlier works such as the anthology comic Eightball (where the cool-girl protagonists of Ghost World originated), lands differently today: In “a world where things were objectively moving in a pretty good direction,” it was easier to make fun of the ascendant mainstream and position himself as a countercultural outsider. Today, though, “I feel like we’re in this great stagnation of cultural thought that I don’t see any way out of,” he said. “I still think it’s funny, going back to it, but now it would be used in a way that’s just adding to the chaos. Now I feel like we need to face the empirical truth.”

The empirical truth Monica needs to confront is the sobering reality of her abandonment, and as she comes to accept why her parents left her, she’s able to let go of what she calls “symbolic coping fantasies.” Clowes, too, is playing with truth-telling, in writing a character like Monica. “I feel like I have this actress that I can get a performance out of, like Ingmar Bergman with Liv Ullmann,” he said. “She’s a version of me, but obviously not me—someone I can project my experiences and some of my worldview onto, and feel safe that I’m not just drawing myself.”

That blend of intimacy and distance is evident in the book, which contains some decades-old ideas pulled from Clowes’s notebooks, as well as concerns that have always been threaded throughout his work. Like Monica, Clowes was partly raised by his grandparents, and he spoke with some awe about how his grandfather was born in 1899 and his son was born in 2004—“two of the people who are closest to me in my life,” separated by more than a century. His grandparents’ house was “preserved in amber from about 1948,” which helped him think about art as a way to merge the old and the new. “In those recombinations, there’s so many endless ways to go,” he said. “As I get older, I’m now aware of all the things I could do—I feel like I’m in control in a way that I never was.” Now, he added in a characteristically dry, mordant tone, “it’s a matter of fighting the clock before I get arthritis or brain cancer.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.