The story tells of a masked figure who joins an isolated band to mount a seemingly hopeless resistance against sinister forces which have seized control of planet Earth.

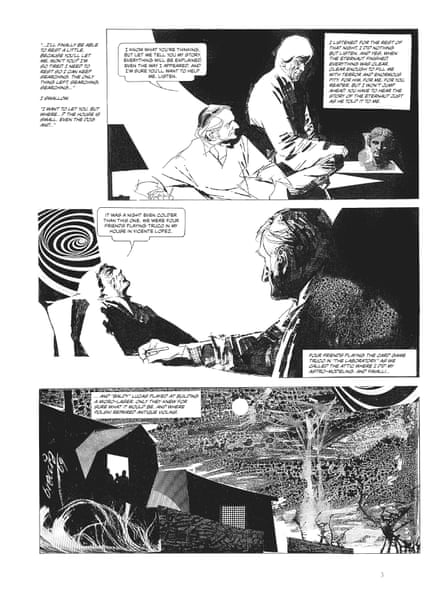

The eponymous hero of Héctor Oesterheld’s comic serial El Eternauta – the traveller through eternity – fights in a world where humans have been turned against each other, and grapples with his own doubts that individuals can make any difference in the face of inhuman horrors.

When it first appeared in 1957, El Eternauta was a work of uncanny speculative fiction published at the high point of Argentina’s gold age of comic books; by the time Oesterheld and his family had been murdered the armed forces in late 1970s, it seemed more like a grim allegory for the country.

At home, Oesterheld has long been a revered symbol of artistic resilience under oppression, and 66 years after its publication, El Eternauta remains one of Argentina’s most-loved graphic novels.

Now, his works are reaching a wider audience with critically acclaimed English-language translations of El Eternauta and Oesterheld’s biographies of Eva Perón and Che Guevara, while filming for a Netflix series based on El Eternauta recently began in Buenos Aires. The series features the Argentinian mega-star Ricardo Darín in the leading role and has a tentative 2024 release date.

But as Argentina heads into a bitterly contested general election, Oesterheld, his family, and his literary legacy have also been dragged into the ugly culture wars fomented by the libertarian frontrunner Javier Milei, and his vice-presidential running mate Victoria Villarruel.

“El Eternauta was a parallel of what happened to Argentina, what happened to me,” said the author’s widow Elsa Oesterheld, before her death in 2015. “My family was destroyed just as our country was destroyed.”

Among the recently republished works is the second part of El Eternauta – an updated and more politicized version originally released in 1976, after Argentina’s armed forces launched a coup d’état.

By this time Oesterheld and his four daughters had become involved in radical leftwing politics – a new resistance not against fictional aliens this time, but against the new military rulers, who murdered up to 30,000 people in the name of battle waged by “Western and Christian civilization” against Marxist unbelievers.

In the space of 18 months during 1976-77 Oesterheld’s four daughters – two of them pregnant – plus their four partners, were murdered by the dictatorship, their exact fate unknown to this day.

Oesterheld’s German surname sounded Jewish to Argentina’s conspiracy-minded military rulers who often singled out Jewish families for extermination. His widow Elsa recalled in an interview that when an army unit broke into her home looking for her husband, they asked if Oesterheld was Jewish. She replied: “He’s not, but if he was, so what?”

Oesterheld went into hiding and continued to release new works from underground, but in April 1977 he was seized, and taken to army’s clandestine Vesubio prison where torture, murder and rape were the norm. He was last seen alive by another prisoner some time around January 1978.

In 2014, three retired servicemen were given life sentences for their part in the crimes at the camp as part of Argentina’s ongoing reckoning with dictatorship-era crimes, which has seen some more than 1,000 convictions – although most of the perpetrators have been released under house arrest because of their age.

But the fragile consensus regarding the dictatorship and its crimes runs the risk of being shattered by a swell of support for the pro-dictatorship, anti-abortion, extreme capitalist agenda of Milei and Villarruel, who repeat like a mantra that they are waging a new battle against “cultural Marxism”.

Villarruel, who has frequently visited former military officers imprisoned for crimes against humanity, has repeatedly trolled victims of the dictatorship, including the Oesterheld family, repeating unsubstantiated allegations of terrorism.

Villarruel says she seeks justice for victims of terrorism, claiming that former guerrillas have gone unpunished for thousands of murders committed in the 1970s.

The facts contradict her. Over 500 people were charged with terrorism in court between 1971 and 1989. An additional 8,625 suspects were imprisoned, some for up to nine years, under state of siege rules between 1974 and 1983.

That is without counting those who never faced trial before they were murdered by the dictatorship. Human rights groups put the number at 30,000, of which 8,629 have been identified by name so far.

Decades after his death, Oesterheld’s ghost seems to have taken on the role of his fictional “traveller through eternity”, reappearing to champion the ideals of resistance and collective action.

“My grandfather’s stories had as their central axis human bonds, human relationships,” says Martín Mórtola Oesterheld, the son of Oesterheld’s eldest daughter Estela, who was shot to death outside her home by a military death squad in December 1977.