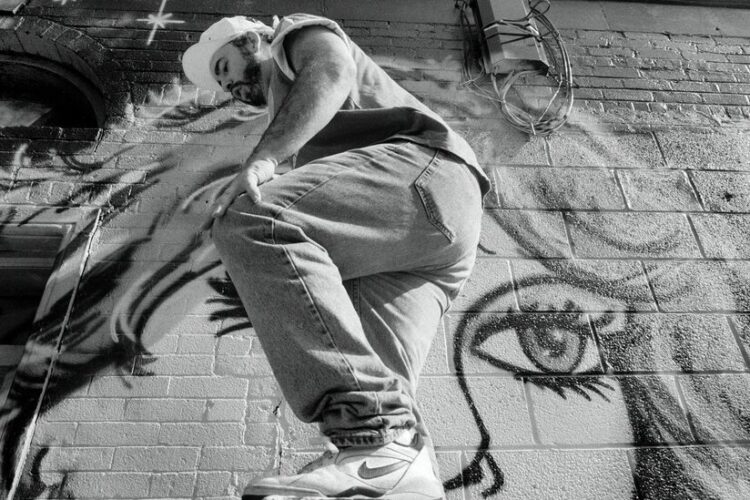

Using the name Tracy 168, he was a pioneering graffiti artist during the tumultuous 1970s and ’80s in New York.

Michael Tracy, a Bronx-bred graffiti artist known as Tracy 168 who turned subway cars into rolling canvases for his spray-paint murals, becoming a breakout star of the New York streets in the 1970s in an outlaw medium that became central to early hip-hop culture, died on Sept. 3 in the Bronx. He was 65.

His death, of a heart attack, was confirmed by his niece Liza Tracy. It was not widely reported at the time.

Mr. Tracy, who started out tagging buses at the end of the 1960s, became one of the most prominent — if anonymous — graffiti artists in the 1970s and ’80s, an era when subway trains slathered in colorful bubble letters and cartoonish images became an internationally recognized visual trope of New York culture.

To some, this explosion of illegal folk art was a bleak symbol of a battered city plagued by lawlessness; to others, it was an emblem of an era of creativity and hedonistic abandon, and one that gave voice to marginalized youth from tough neighborhoods who otherwise felt they had little.

Many New Yorkers reviled the work of Mr. Tracy and his colleagues. But they could scarcely miss it. “More people saw my work than you could put in any museum,” he said in a 2017 video interview. “Those subways made me a superstar in New York.”

Mr. Tracy brought his own spin on the typography of subway painting, sometimes rendering his name in letters that looked as if they were on fire. He was also known for his spray paintings of cartoon characters like Yosemite Sam and the Flintstones, in addition to his own stylized self-portrait featuring a bushy-haired young man wearing Jetsons-esque sunglasses and a can’t-catch-me grin.

“When all the teenagers were just writing their names on walls, he evolved and went bigger, painting murals and characters and portraits,” Alan Ket, a former New York graffiti artist and a founder of the Museum of Graffiti in Miami, said in a phone interview. “He brought an art element to what before was just tagging.”

As rap music, break dancing and D.J.ing moved from informal neighborhood jams to the mainstream, graffiti was enshrined as another pillar of broader hip-hop culture. But Mr. Tracy often pointed out that he started writing in the hippie era, when he was listening to artists like Sly and the Family Stone.

“First we started on buses, a bunch of psychopathic kids from school hitting up our names during lunch, not realizing what we were doing,” he said in an interview with the site Subway Outlaws. He added, “We were like flower-power kids acting out of rebellion to things like the Vietnam War.”

He and contemporaries like Taki 183, Cay 161 and Phase 2 rarely used the term graffiti, dismissing it as something created by the news media. They simply referred to themselves as “writers” — and for some, they were something more. “I was always an artist,” he said. “I just had to find another medium, which was the train.”

Authorities had a very different view. By 1973, the city was spending $10 million a year (nearly $70 million in today’s dollars) to combat the spread of graffit without making an appreciable dent, The New York Times reported.

The next year, however, Esquire magazine would declare graffiti “the great art of the ’70s” in a cover essay by Norman Mailer.

As Mr. Tracy put it, he was performing something akin to a public service. “We took these dull, boring-looking subways,” he said in the Subway Outlaws interview, “and we turned them into something beautiful, like a rolling stock of rainbows.”

And in a city plagued by arson and teetering on the brink of financial ruin, he argued, people needed it. “It gave people something colorful to look at on a gloomy day in the city,” Mr. Tracy said. “Whenever the mayor took his trips to Florida, there would be a transit strike or a garbage strike. Everyone was just stuck, so we helped take their minds off the horrors in their life.”

Michael Christopher Tracy was born in Manhattan on Feb. 14, 1958, to James Tracy, a truck driver, and Florence Martinez.

In his youth, he divided his time between his maternal grandfather’s apartment in Manhattan and his parents’ apartment on 165th Street in the Bronx, near Yankee Stadium, although when he chose a moniker to hide his identity from the authorities, his sights wandered a few blocks north. He added 168 to his last name, he said, because he preferred the sound of it.

Mr. Tracy’s Bronx neighborhood, he recalled, was a patchwork of territories belonging to gangs with names like the Ghetto Brothers and the Savage Nomads. “You walk one block and you have to fight a whole neighborhood,” he said in the 2017 interview — although, he added, some gangs eventually paid him to paint their colors on their jackets.

As his graffiti pursuits took off, he tried to dominate select subway lines, including the 4 train. “In the early 1970s, my name was on every IRT train that pulled into a station,” he said, using an archaic subway term. “I was all-city.”

The risks of this illegal art form were obvious, involving foot races with police officers and various high jinks involving moving trains. “This is the first art form where you could be killed,” he said in an interview for the documentary “Just to Get a Rep.”

Then again, he loved to court risk. “Every day, I needed to see the grim reaper,” he once said. “Otherwise I wasn’t alive.”

In the mid-1970s, Mr. Tracy formed an influential graffiti crew called Wild Style with seminal graffiti artists like Pnut 2, King 2 and Chi Chi 133 who became known for their colorful, abstract imagery and for complex letter styling that was often illegible to the uninitiated. The term “wild style” later became a catchall designation for such expressionistic, graphically ambitious graffiti, Mr. Ket said, as well as the name of a 1982 feature film that many consider the first hip-hop movie.

In the early 1980s, Mr. Tracy began to cross over into the fine-art realm, selling his work in galleries as graffiti became an art world fascination, Mr. Ket said. That bubble burst within a few years, but his work was later featured in exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.

Mr. Tracy eventually made ends meet by painting murals on commission for Bronx pizzerias, bars and even a chain of funeral homes, as well as by selling his paintings on the street, Mr. Ket said.

His survivors include his brother, John; his half brothers, William Tracy and Joseph Denault; his half sisters, Eleanor Martin, Gloria Tracy, Michelle Dillon, Maureen Peoples, Patricia Orlando, Virginia Dauterman and Tracie Ann Orozco; a son, Shawn; and a granddaughter.

In interviews, Mr. Tracy acknowledged that art-world fame was never his goal. Still, he said, he hoped that his work would live on.

“I used cartoons,” he told Subway Outlaws, ”because cartoons never die.”

“Cartoons,” he added, “are really establishing the fact that my name will live forever. I guess we were all looking for immortality.”