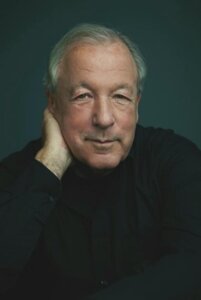

A promotional poster for Miklós Vámos was defaced with a Jewish star in Hungary Courtesy of Miklós Vámos / Forward Montage

A large poster advertising a new book of mine was vandalized at a bus stop in Budapest a few years ago. Someone scrawled a Star of David on my face.

I suspect the hooligans who did this had no understanding of their actions. I blame those who influenced them, who underhandedly put them up to this. If the vandals or their minders had an iota of decency and intelligence, they would not have defaced a poster that advertised a book, let alone mine.

Ever since my adolescence, I have felt as if I were living in a relatively comfortable state correctional facility called Hungary. Unfortunately, I often feel the same these days. Instead of moving forward, my country is fast becoming more isolated and politically narrow-minded. Its current government is in its fourth consecutive term.

During their time in power, our leaders have managed to turn their once-democratic views into right-wing vitriolic nonsense. Only a few newspapers and other media outlets in all of Hungary are entirely truthful, without traces of censorship. It has become nearly impossible to criticize the government that has successfully brainwashed its devotés over the years.

The word “liberal” used to be considered a compliment in Hungary. Nowadays, it is considered a swear word. Libernyák, a derivative of the term, is used as an insult in the National Assembly and throughout government-supported media. A hurtful variation of the term, libsi, rhymes with bibsi, derived from a hateful term for Jews.

One of seven survivors

I grew up in what my generation would call a typical Eastern European family of gemischter salat, or mixed salad. My ancestors on my father’s side were Jews who wanted to lead a simple Hungarian life, but were prevented from doing so by fascism. Tragically, they perished in the Holocaust. Fortunately, my father — a member of a penitentiary march battalion of Jews — survived.

Out of the 5,000 Hungarian Jews sent to their deaths late in World War II, only seven came back. My father was one of them. By the time of my birth, my father and the small family he created claimed no religion.

I was raised in Socialist Hungary unaware that I was a Jew. I learned of my Jewish ancestry only once I entered adolescence and, further contributing to my emotional hardships at the time, my father died when I was 19.

In an effort to save myself from his chaotic heritage, I found an outlet in writing short stories and novels.

At the beginning of the 1980s, I had a column in one of Hungary’s most prestigious literary magazines, Élet és Irodalom (“Life and Literature”). It was called “Our Never-dispatched Foreign Correspondent Reports from Abroad.”

This was my covert objection against a grotesque political system that not only did not dispatch me anywhere, but wouldn’t even let me leave the country on my own terms. Forty-ish years later, while much has changed within my homeland’s political system, much also has remained the same.

In the 1980s, the average citizen was allowed to go abroad once every three years. I, on the other hand, didn’t hold a passport. The authorities had denied me one for what they claimed were political reasons. I had been a member of a band that dabbled in protest songs; I wrote the music and lyrics to some of our ditties that the authorities claimed criticized socialism. They did, but in a rather subtle way that I’d hoped would go under the noses of the authorities. They did not, and they were censored.

“To hell with all of you,” I thought, and so began to report from “abroad” without ever leaving my home. I did not write about actual news; instead, I tried to paint a picture of how I imagined the Western world outside the borders of my fatherland.

Nowadays, while I indeed have a passport, I feel like I have been thrown back into the past, a time when I “reported” made-up scenarios from far-flung places because I hadn’t the choice or ability to get any place.

For my column in the 1980s, I dispatched a report as if I were on-site, in Paris, covering the then-presidential elections in France. I once wrote another as if I were at the Vatican, covering the new Pope. Just as an accredited journalist with a passport would.

But the story about the French elections was conducted from my hometown of Budapest. To bolster its interest, I wrote a piece, both true and thinly veiled, about what it felt like to miss being present for the elections. I did so through the eyes of a young French woman I knew through a friend. She’d been spending time in Hungary (as an accidental tourist) and was unable to return to France in time to cast her ballot and missed the election. She was devastated.

I was perplexed, unable to understand why casting her vote was so important to her. She gave me a thorough explanation of the French election system and what it meant to her: She believed she had an actual say in the current political moment of her native country. By extreme contrast, I had never believed such a thing was allowed or ever could be possible for me here in Hungary. And that’s when I understood what democracy meant, and that it was a foreign concept to us Hungarians.

A sea of propaganda posters

Today, Hungary has a sea of propaganda posters plastered all over the country, targeting various “enemies” of the state. For years, it was George Soros’ head on the chopping block, despite his many donations to the country, its institutions and intelligentsia, including a generous scholarship from his organization that made it possible for Prime Minister Viktor Orbán to study in England during his college years.

The prime minister has no shame in turning around and biting the hand that fed him. To add oil to the fire, a high-ranking individual representing a non-governmental organization publicly called George Soros “the liberal Führer” and Europe “George Soros’ gas chamber.”

Thanks to the long and rampant anti-Soros campaign, among other tactics, the country has not yet fully grappled with its role in the Holocaust, and some of its citizens have committed antisemitic acts in the most unexpected places.

While I’d saved myself from my tragic past through writing, it was that writing that inspired someone to deface my Jewish heritage — many years after the fall of socialism, in the heart of modern-day Budapest. My themes aren’t all Jewish in nature; must I only be denigrated in Hungary as a Jew?

To add insult to injury, instead of using incidents like mine as a teachable moment, the Orbán regime stays mum and continues to make enemies with artists and writers, among others.

I do not need the regime’s support. But it would be important for Orbán and his allies to react in a humane and appropriate manner when antisemitism rears its ugly head, especially publicly. Given the outsize influence Orbán has been enjoying outside Central and Eastern Europe, were he to call a resurgence of Nazism by name, he could influence his easily influenced citizenry that antisemitism simply is bad.

Without gainsaying antisemitism, the Western world may think Hungary seriously means its antisemitic slogans and tacit support of antisemitic acts, even if they only use them to create a common enemy — which is a frequently preferred tactic in dictatorships.

Barring Orbán and colleagues’ public refusal to disavow antisemitism, I often write today through a Jewish lens, in part to spite them and those of their ilk. Two years ago, after having written a number of books devoted to processing my complex feelings and sorrow around the Holocaust and my relatives who’d been killed in death camps, I concluded that my oeuvre thus far was not enough.

I wrote another novel called Dunapest that chronicles the dangerous months in 1944 when the Nazi regime tried to kill every Hungarian Jew who was still alive and not yet deported. Many of them rounded up that terrifying year were shot and thrown into the Danube River. Two foreign diplomats worked tirelessly to save them: the Swede Raoul Wallenberg and the Swiss Carl Lutz. They became the protagonists in this work of historical fiction.

Upon my book’s publication, every government-controlled media outlet pretended the novel did not exist. Unelected Hungarians, however, lapped it up — it is in its fourth printing — and sales continue to be brisk. I can postulate its popularity among the populace is due to its subject; I am airing Hungary’s dirty WWII laundry that people know is filthy and desire to know more about it than they may already. My story allows them this liberty.

Despite my personal ties to the Holocaust, coupled with my knowledge of the history of Hungary and European Jewry, my byline is not welcome on the pages of a number of newspapers and magazines, which are backed openly or clandestinely by the government and its foundations.

Ironically, this sometimes makes me feel like I am back in the not-so-relaxed atmosphere of my adolescence. By the time I was 15, I played in two rock bands, including the one alluded to above, Gerilla, a protest band. Thanks to my dissident lyrics I was not allowed to attend university for a year because of my “political sins.”

Today, I still have to remind myself that, in the eyes of the government, as a successful novelist, I am heavy artillery along with others within the Hungarian literati; naturally, thus, they want to censor me.

I am a novelist who thinks with an open mind. My books usually take years to write; when I write for extended periods, it can feel like I am shut off from the world.

In 2023, it’s cold here, and not only because of the lingering gas and electricity crisis. These are chilling times. I try to make ends meet with my pen (and also with my typewriter and computer). I can only hope that I won’t have to turn back into a never-dispatched foreign correspondent who reports on the events of the world while my world is stuck in here.

To contact the author, email [email protected]