With high profile strikes by the Screen Actors Guild and the Writers Guild of America raising awareness of issues surrounding low payment, poor healthcare this summer, and a lack of job security in the entertainment industry, it’s raised the obvious question: why don’t comic creators have their own union or guild to protect them? After all, it’s not as if the comic book industry isn’t dealing with the same problems. The truth of the matter is, a comic industry union has been tried more than once, but it’s never quite worked out.

Unions as a front for Communist activities, and other stories

The first recorded effort to create an organized labor movement amongst comic book professionals happened in the early ’40s, according to none other than Jim Steranko; an off-hand mention in his iconic The Steranko History of Comics — an oral history compiled, curated, and published by the artist in the early ’70s — mentions that the Communist Party of the United States of America attempted to create a union of comic creators, only for the very first meeting to be broken up by Plastic Man creator (and editor for Lev Gleason Publications, not coincidentally) Jack Cole.

This account, which has never been backed up by another source, may be apocryphal, as much as it’s simply a good story that we want to be true. If nothing else, the comic book industry of the period was arguably ripe for unionization — not only was the US more pro-labor in the early 1940s than, arguably, at any other point in the last century, but the comic book industry was both new enough, and full of enough full-time employees, to make it a real possibility.

Even if the communist-plot union story turned out to be untrue, there really was something in the water at the time; legendary artist Joe Kubert has spoken in interviews about meetings about creating a comics union in the late ’40s, with creators complaining about poor page rates and looking for better health benefits. The more things change, the more they stay the same, apparently; those are the same concerns cited by creators throughout the history of the industry when seeking to band together to better their working conditions.

National unrest and creators who didn’t know their place

Certainly, those were the primary concerns behind a ’50s attempt to unionize by creators at National Comics, which would eventually become DC; talking in a piece that appeared in TwoMorrows’ Comic Book Artist #5, writer Bob Haney said that the effort was “squashed in the most horrendous way,” explaining that “people were just kicked out” of the company for their effort. A similar effort in the mid-’60s at the same company ended, on the face of it, differently, but the final result was essentially identical: when a group of creators including Haney, Arnold Drake, and artist Kurt Schaffenberger got together asking for better page rates, royalties for reprints, and healthcare, it led to a standoff with management that fell apart when the creator group splintered over whether or not to go on strike. (“I did not think we had a chance… plus, I was building my house, and the strike was coming at the very worst time for me personally,” Haney told Comic Book Artist. “This does not reflect any credit on me,” he admitted.)

Although it looked as if National got what it wanted without the need for any punitive measures, the creators involved believe the latter happened anyway. ‘I don’t think [the writers] were fired so much as they were starved out,” Arnold Drake said in the CBA piece, saying that editors at the company “took titles away from them, and they would put them on lesser books. There was a process — whether it was conscious or otherwise — of kind of stripping the guys of their own dignity.”

1970 saw the establishment of the Academy of Comic Book Arts, an organization consisting of comic book professionals that never seemed entirely sure whether it wanted to be the comic book equivalent of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences — better known as the organization that gives out the Oscars every year — or a fully fledged union. The group’s first president, one Mr. Stan Lee, certainly favored the former, but Neal Adams, who’d inherit the position, was looking towards the latter. (“I can’t tell you how many times Martin [Goodman, Marvel publisher] would listen to some of the things Neal Adams was saying and mutter, ‘Who the hell does he think he is?,’” historian Jeff Robin recalled in Comic Book Artist #16.)

No wonder, then, that Adams would be one of the primary movers and shakers behind the Comic Creators Guild, a short-lived organization created in 1978, a year after the Academy fell apart.

Demands for better pay and conditions start to bear fruit… but why?

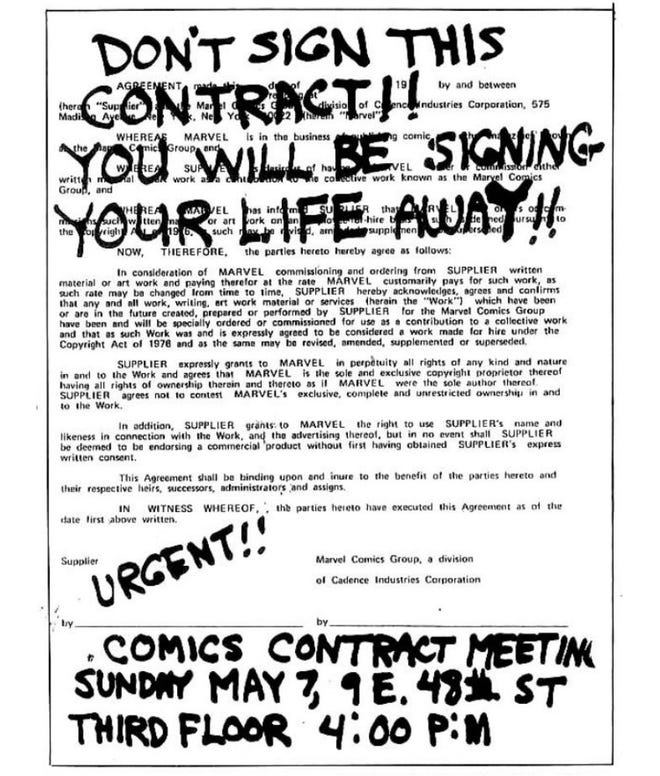

An outgrowth of Adams’ regular creator get-togethers at his Continuity Associates studio, the CCG was formed in reaction to a change in U.S. copyright law in 1978, which prompted new contracts from publishers that claimed copyright in perpetuity for work produced by talent. The new contracts were points of controversy in the creative community, to the point where a flier for the first meeting of the CCG reproduced a page of the Marvel contract with “DON’T SIGN THIS CONTRACT!! YOU WILL BE SIGNING YOUR LIFE AWAY!! URGENT!!” scrawled over it.

The intent of the CCG, according to a statement read at that first meeting, was “to become recognized as the sole bargaining agent for the freelance talent working in the comic book industry.” (To this end, it published a suggested rate card for freelancers, which included $100 per page for writers, and $300 per page for artists, both for first publication only. More than four decades later, some publishers are still paying around this amount.) Such a purpose, however, would have required a more focused, organized body than the CCG turned out to be; despite the best intent, the group fell apart within a couple of years without affecting much change in the industry as a whole.

Or… perhaps not. After all, DC initiated a new royalty program in 1981 – the work of publisher Jenette Kahn, who cited Neal Adams’ influence in her decision – which pushed Marvel into following suit a month or so later. Both publishers would similarly start experimenting with new formats, new genres, and allowing creators to maintain some level of ownership or financial participation in their work across the next decade or so, perhaps explaining a lack of notable unionizing effort amidst the creative community following the collapse of the Comic Creators Guild – although it’s also possible that creators had simply learned to negotiate in different ways: consider the formation of Image Comics as an example of creators taking more direct action when it comes to getting what they wanted.

Comics’ first unions arrive, decades after the first attempt

Ironic, then, that it was Image that produced the comics industry’s first official union: Comic Book Workers United, announced in 2021 and ratified in March 2023, as staffers at the publisher organized for better working conditions and pay. The group’s formation inspired the creation of a second union at manga publisher Seven Seas Entertainment, and talk of similar groups at other publishers, but it remains to be seen how successful it has been at its originally stated aims; the union filed complaints against Image in June, alleging that members were being targeted for mistreatment.

In terms of something more akin to a creators’ union, more attention should be paid to the Cartoonists Cooperative, an organization — not a union, because the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 doesn’t allow independent contractors (freelancers, in other words) to legally unionize in the U.S. — announced in February 2023 with the intent of supporting cartoonists and comic creators, both in terms of promoting their work and fighting for better rates and industry-wide standards. As committee member Reimena Lee put it in their opening statement, “The lack of centralization and organization in the comics industry has made it difficult for working cartoonists to share resources and knowledge – even more so if one is marginalized, young, disabled, part-time, or/and overseas. The Cartoonist Collective is built in solidarity with our fellow creatives who exist outside the margins; we aim to empower each other to go beyond the walled gardens, algorithms and corporate market pressures that have dominated the comics scene today.”

Although only a few months old, the group already boasts more than 600 members, and has established an active online presence through its site, newsletter and Discord forum. Perhaps more than any other, this is a group that is aware of the past that it’s trying to break away from — it’s worth noting that another committee member cited the short-lived Cartoonist Co-Op Press from the ’70s in an early interview — and has the drive to push towards something better.

Even with steps forward finally being taken, however, the road to true change in the comic book industry will require the input and participation of publishers as well as cartoonists and staffers… a difficult truth that will, if anything, most likely make the need for collective action and a united workforce even more necessary. The road that lies ahead remains a long one, unfortunately.

Learn more about CBWU’s complaints against Image Comics.