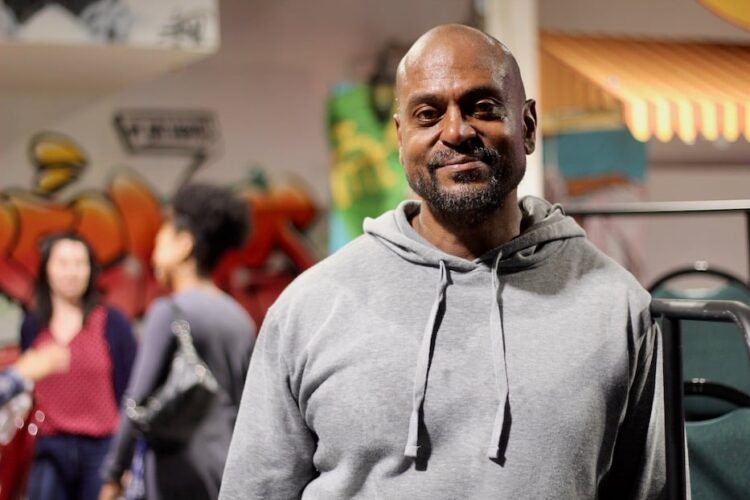

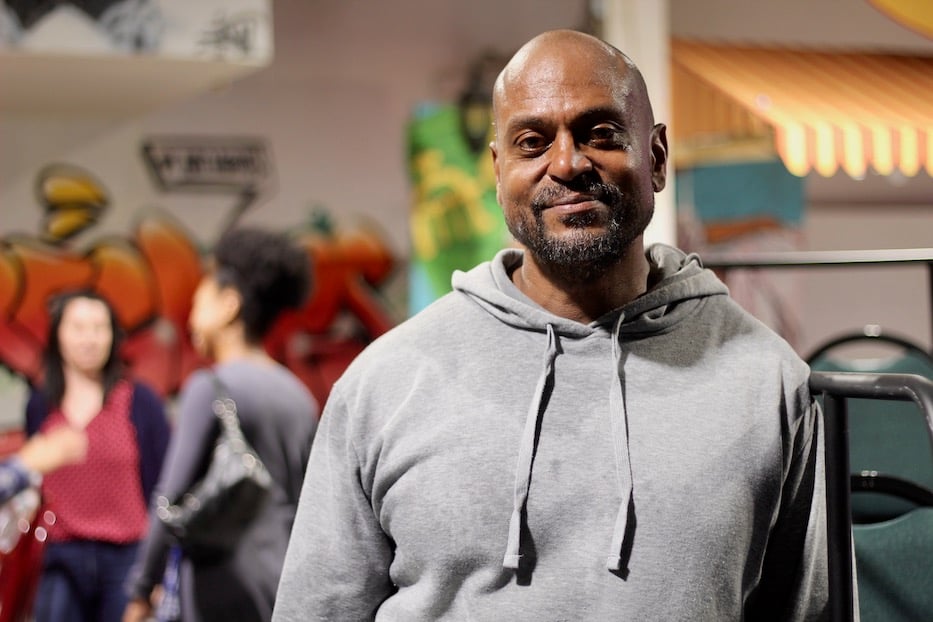

Riggins at Bregamos Community Theater. Lucy Gellman Photos.

In one universe, a young Terrence Riggins is up against two school bullies, about to receive a beating when a miracle happens. From down the hall, his middle school crush comes running, begging them to stop. Her arms glide through the air, and even in a fog of fear, she is perfection. Riggins holds his breath. She’s matter-of-fact: Don’t beat up a kid who was good in the school play. He exhales.

Back in the present, the light shifts, and Riggins steps forward. Around him are the bare bones of a solitary cell. “Acting didn’t get me the girl, but it definitely saved my ass,” he says. There’s a beat. “Maybe it can save my life.”

The sheer and persistent power of theater—and its ability to show up as a source of salvation—sits at the wildly beating heart of Unbecoming Tragedy, an autobiographical play from writer and performer Terrence Riggins that is now growing its roots in New Haven. In roughly 60 minutes, it tells the story of Riggins’ life and long relationship with the stage, leaning into all the complexities of being human, Black, male, and an artist in a country that still has not made space for those intersecting identities to soar.

Last weekend, a workshopped performance from Collective Consciousness Theatre (CCT) and Long Wharf Theatre (LWT) landed at Bregamos Community Theater for two nights only. Directed by Cheyenne Barboza with assistance from Finn Wiggins-Henry and Valerie Badjan, the work doubled as a testament to not only Riggins’ tight and affecting writing, but also the importance of theater as a form of healing and of education. Further performances in the community have yet to be announced.

“I felt that I could not move forward in my theater career or my acting career if I did not write this play,” Riggins said in a phone interview before hours of rehearsal. “I cast myself in the story of my life. I’ve done other people’s plays, I’ve done other people’s projects, but I’ve never done my own. I’m not afraid of serious catharsis and gravitas and pathos. And I had to use my life and my vulnerability in order to achieve that.”

“This is not a solo show,” he added. “This is a play. It’s also a ritual.”

And it is. Conceived when Riggins was in solitary at the Cheshire Correctional Facility several years ago, the work begins and ends in a single cell, the playwright constantly blurring the lines between perception and reality, the way one’s mind can bend sometimes, and break at others. In between, he tells the story of his life in lyrical, sometimes raw and unflinching detail, allowing moments to shift in and out of focus so often that they melt into each other.

For instance: early in the show, his present becomes an affecting fade into his past, jumping between decades with quick, crisp rhythm. As the actor enters the cell and lays his body down, sleeping fitfully, he mutters in his sleep, drawing the audience in close to listen to his half-conscious ramblings. Around him, the set is minimal—a bed, sink, tube of toothpaste and floor where he works out fanatically. So when he wakes and begins speaking to a grayscale portrait of his mother, something falls right into place.

Moving from the bed to the floor to a sink, he turns the clock back to a childhood in 1960s Los Angeles, where he spent his youth learning among Black nationalists. Riggins has a gift for clear language—”I was a boy, once,” he says with the same weight that one might deliver a cancer diagnosis—and listers can see siblings dressed in dashikis, a young Terrence learning Swahili and West African dance as he moves through a world.

It’s here that one can also feel a tension rising, between Riggins the will-be actor, the empathic artist, and Riggins as the threat the white world already perceives him to be (or in his words, “becoming tragedy”). Jump forward, and the Black revolutionaries he looked to are dead, leaving him grappling with a system that is broken. Forward again, and he’s discovered Joe Turner’s Come and Gone in an L.A. prison, suddenly aware of the mesmerizing power of August Wilson’s words. Forward once more, and his daughter is born while he is playing Caesar Wilks in Gem Of The Ocean.

That his heartache and his joy live side by side is part of the performance. Often, he is rocketed back to the present, in dialogue with the cell. Each time, it brings the audience back to a sort of harsh reminder of the world that is (overly punitive, especially of those who are Black and male before they are human) rather than the world that could be (restorative and rehabilitative, rather than a literal cage).

It’s this that makes the show so immediate, using theater as a vehicle to amplify both memory and the splintered system in which Riggins and his audience live.

“Well damn brick face!” he says at one point, and the audience can see the smallness of the cell, the way its design is meant to feel like it is closing in on a body. “You just became my fourth fucking wall!”

What makes Unbecoming Tragedy stand out is Riggins’ ability to marry matter-of-fact storytelling with deep feeling, tight and cheeky lyricism, and a physically powerful performance. From L.A. to New York City, from parochial school to his father’s passing, he works through vignettes of his life, always returning to theater as a level set and an unmatched balm.

Sometimes, he is Riggins but he is also Othello, wronged by both Iago and the world. Sometimes, he is Riggins but also Paul Robeson, collapsing decades of struggle in a few single verses of “Ol’ Man River.” Sometimes he is Riggins and also Herald Loomis, trying to find his way in a country built by stolen people on stolen land.

Sometimes, he is just Riggins, and he is just surviving. It has the intended effect: his art and his life are often porous, flowing in and out of each other until they have become intractably tethered.

The writing, paired with an intensely physical performance, carries the show. Riggins is a master of narrative, with an ability to knit humor, storytelling and verse that feels rare and sacred (he has studied Wilson’s work meticulously, and it shows). His descriptions are not only evocative but often poetic (describing a fight with a fellow inmate: “this scuffle is more of a war dance.” On the vicious cycle of addiction: “My body is heavier and denser than all the water in the world.”)

It allows him to tap into a sort of time-hopping and magical realism that propel the play. At multiple points throughout the play, a prison wall becomes a screen onto which Riggins’ memories are projected, his description so vivid that an audience can all but see them in real time. There is Riggins’ daughter, her smile a beacon of light as the camera flashes. There are his siblings, frozen in time. There is his mother, witn an opal necklace he bought her for her birthday.

It’s this that makes the work so intimate: Riggins’ delicate touch is on everything, and so is his fearlessness, which persists even when every eye in the house is on only him. Nowhere, perhaps, is that clearer than in a sequence near the end of the show, when Riggins works through a thick fog of grief, eulogizing his mother after trying to get back to her in a place that has been built not to move. It’s here that something clicks, pulling him out of a half-conscious state and back into the present, with all its ugliness and baggage and also its potential.

“You gon’ be alright man,” he says, and the audience knows that it’s true. “You belong in the world. Just like the water and the rambling river.”

While it is told from solitary confinement, Unbecoming Tragedy is not a play about abolition or the futility of the carceral state, although Riggins the actor has taken on both during his decades on the stage. Instead, it is a show about deep self-exploration, self-interrogation, and at times self-flagellation—and the sheer force of one man’s human-ness in a system that does not make room for second chances.

It’s this, he said in an interview before the play, that he’s still sitting with as he continues to work on the show. After years of moving—he has lived in Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, Alaska, Texas, Massachusetts and Connecticut—Riggins said he feels a sense of rootedness in New Haven that’s still relatively new to him. That sense of being home is carrying him forward—and has helped bring the work to fruition.

“It’s just another journey,” he said. “It’s another way of looking at the world. It’s a kind of a different, unusual ironic journey of a human being trying to figure it out, as we all are. Just trying to make sense of their lives.”