As a commuter tried to make out the words of Richard C. Shaner’s “Gilman Pond Mountain,” someone walked right over it.

Engraved poems line the brick floor of the Davis Square MBTA station. Installed in the 1980s shortly after the station was initially constructed, the poems range from classics by Walt Whitman and Elizabeth Bishop to a short poem on the “free will” of tomatoes by Peter Payack.

These poems are a part of the MBTA’s greater Arts on the Line project. Inspired by art installations in subway stations around the world, Arts on the Line pioneered the incorporation of artwork into subway systems in the United States.

Partially funded through a $45,000 grant from the Federal Transit Administration (formerly Urban Mass Transportation Administration) and a $70,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, Arts on the Line served as a pilot program for public art in the transportation systems of other American cities.

The MBTA and Cambridge Arts Council worked together to integrate art into each Red Line station. Alongside the construction of the Red Line Northwest Extension from Harvard to Alewife, each new station included multiple pieces of public art, including sculptures, murals and stained glass.

Sarah Firth / The Tufts Daily

“The House by the Side of the Road” by Sam Walter Foss is pictured at the Davis Square station.

Since the poems at the Davis Square station are less flashy than the visual art in the rest of the station and of other Red Line stations, the poems go unnoticed by some while are beloved by others.

Birgit Wurster, the MBTA Wayfinding Designer and current manager of the art program on the T, wrote in an email to the Daily about a favorite poem.

“My personal favorite of the series at Davis is the Emily Dickinson poem [“I’m Nobody! Who are You?” (1891)] for the way it speaks to feelings of both anonymity and interconnection that I associate with being in the shared spaces of the city,” Wurster wrote.

Lane, a commuter at the Davis Square station interviewed in passing, said that the poems speak to more than just their subject matter.

“I think they’re pretty neat,” Lane said. “It shows that there’s maybe investment in the community, from maybe the local government or the folks who live around here.”

However, weathered by over 40 years of footsteps, the poems are often hard to make out. Some commuters who frequent the station may not have noticed the poems.

Ali and Rohit, two commuters interviewed at Davis Square, told the Daily that they take the Red Line every day, but that they had never stopped to look at the bricks beneath their feet.

“This is the first time [I’m reading them],” Rohit said.

The poetry’s indiscernibility makes it difficult at times for commuters to appreciate the intentionality in the station’s design.

“This poem kind of camouflages with the floor, which isn’t great for visibility,” Ali said.

Lane added that they originally thought the poems were spontaneous.

“Admittedly, I kind of thought it was just someone who wrote them on the floor and was just doing whatever they wanted, but apparently not,” Lane said.

While the poems were officially installed, several embody the experimental free spirit that Lane commented on.

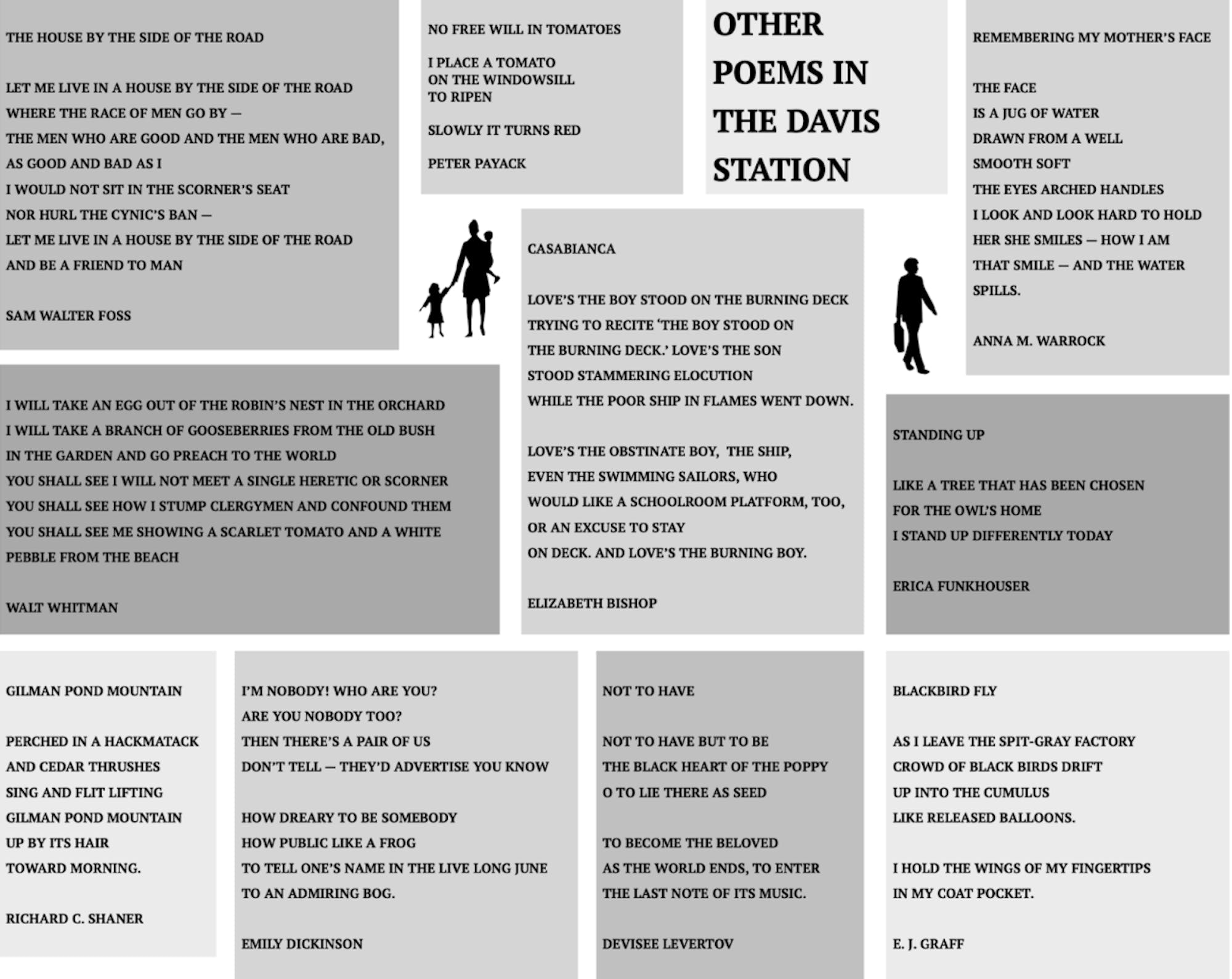

Graphic by Sarah Firth

The complete collection of poetry displayed throughout the Davis Square station.

This is true of the untitled poem, “At 7 a.m. watching the cars on the bridge” by James (Jim) Moore, which is engraved at the far end of the station.

In the poem, the narrator expresses that while everyone else is going to work, they are choosing not to.

Moore, the author of the poem, shared his intentions behind it in an email to the Daily.

“I guess my intention was to make some sort of statement about being outside the system. Freedom, I suppose,” Moore wrote. “Though again, it was a long time ago. Not really sure what my intention was.”

Moore was a graduate student at the time of writing the poem “At 7 a.m.,” which includes countercultural themes. In 1970, shortly after the publication of the poem, Moore served 10 months in prison for evading the Vietnam War draft.

“Looking back on it now, it seems sort of juvenile to me,” Moore wrote. “I mean, why should I be bragging about not having to go to work when so many did? The intent was, I think, a good one. But it is not a poem I would ever write today. It seems insensitive about the reality of most peoples’ lives.”

When a poem is displayed in a public place, readers may interpret the poem in different ways. The environment of the place and diversity of the people who interact with it all influence a person’s reading of a public poem.

Sarah Firth / The Tufts Daily

A poem engraved into the platform floor at the Davis Square station.

John Lurz, an associate professor of English at Tufts, commented on the role of location in his interpretation of Moore’s poem.

“I have an image of someone who is unemployed, who is sort of outside the social contract, who’s being forgotten and left behind in a certain way,” Lurz said. “That was my first impression, partly because there was a homeless person in that space with me as I was reading this poem.”

However, after reading it a second time in a photo rather than in-person at Davis Square, Lurz thought the tone of the poem was more rebellious and playful.

“When I read it on the screen, I got more of this possibility of a more playful … ‘I’m not going to work, I’m not playing this game’ … as almost an aesthetic experience,” he said. “I wondered, had there been a bunch of teenage kids horsing around there, if I would have had this more playful response first rather than later.”

At the Davis Square station, the poems are all engraved into the brick floor. Lurz believes this choice forms part of the poetry’s appeal and accessibility as public art.

“You’re literally above the poetry,” Lurz said. “It’s not coming down at you like it would be coming from a place of authority or a place of elitism.”

Ultimately, investment in public art can add worthwhile enhancement to any ordinary space.

“I’m always a fan of anything that can put art and literature sort of in touch with our everyday experiences,” Lurz said.